Introduction

Complete report here or read it at Common Cause

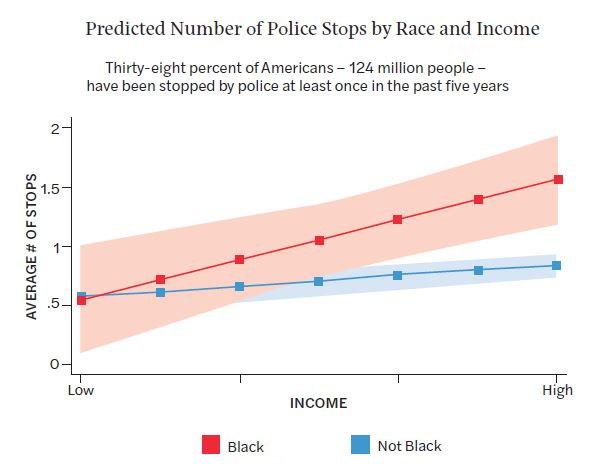

Common Cause: Thirty-eight percent of Americans – 124 million people – have been stopped by police at least once in the past five years. In prison, on probation, and on parole, 6.7 million people live under court-ordered supervision.

Millions more convicted of felonies experience long-term or even permanent effects of their encounters with the criminal justice system through disenfranchisement and housing and employment discrimination stemming from the required disclosure of their past convictions on applications. Mass criminalization and incarceration, often targeted at African-American and Latino communities, disenfranchises and disempowers millions of Americans and undermines the legitimacy of our democracy.

Despite its broad reach, many Americans view our criminal justice system through a distorted lens. Popular understanding of the system follows narratives created by movies and television shows.

Programs like Law and Order tell their stories from the perspective of scrupulous detectives and prosecutors who exact tough justice on deserving criminals. The reality often is starkly different. The television shows typically do not feature scenes of officers arresting people of color for petty crimes only to boost arrest statistics and qualify themselves for promotion and their departments for state and/or federal funding.

Nor do the shows use airtime to highlight how many communities are politically underrepresented because every 10 years the census counts incarcerated individuals as residents of their prisons rather than their home towns.

And it rarely makes compelling television to depict a judge locking up a defendant simply to bolster the judge’s “tough on crime” reputation for their reelection campaign, or to show the judge raising campaign funds from special interests that profit from mass incarceration. All of these actions significantly hinder access to democracy for many communities, especially those suffering from poverty, communities of color, and persons with disabilities.

Source: Cato Institute, “Personal Contact with the Police and Justice System,” https://www.cato.org/policing-in-america/chapter-3/personal-contact-police-and-justice-system.

The criminal justice system is neither as simple nor as just as depicted on television. On the contrary, it’s a very broken system.

The system is shaped by many of the same political forces that distort and corrupt other areas of government policy and action: the influence of special interest money in elections and lobbying of our elected officials, partisan disputes over voting rights and redistricting, abuses of power, and ethical breaches.

Mass incarceration is a fundamental threat to democracy. A society that unjustly criminalizes and imprisons so many people, devastating our families and communities, and disproportionately targeting people of color and those impacted by poverty for policing and punishment, is not a society living up to its claim that everyone’s voice matters. Between the mid-1970s and 2017, America’s incarcerated population of 250,000 exploded to 2.3 million, the most in the world. The 700-plus percent increase came as the nation’s total population grew by less than 50 percent.

Many policy choices are responsible for the steep increase. Mandatory minimum sentences give judges few options to tailor punishments to individual defendants’ circumstances; truth-in-sentencing laws limit parole eligibility – even for people who have been rehabilitated – and “three strikes” laws can inflict disproportionately extreme sentences on those convicted of three crimes.

Though violent crime in the United States has decreased by 51 percent and property crime has fallen by 43 per-cent since 1991, incarceration rates do not reflect this decline. And while the number of people incarcerated has dropped roughly one percent per year since 2007, the US still imprisons more individuals than were enslaved in the antebellum south.

Source: Diane Whitmore Schanzenbach, Ryan Nunn, Lauren Bauer, Audrey Breitwieser, Megan Mumford, and Greg Nantz, “Twelve facts about incarceration and prisoner reentry,” Brookings (October 21, 2016), https://www.brookings.edu/research/twelve-facts-about-incarceration-and-prisoner-reentry/

There’s little evidence this high rate of incarceration explains the decrease in crime; in fact, research shows that incarceration is more likely to increase the likelihood of relapse into criminal behavior. ,

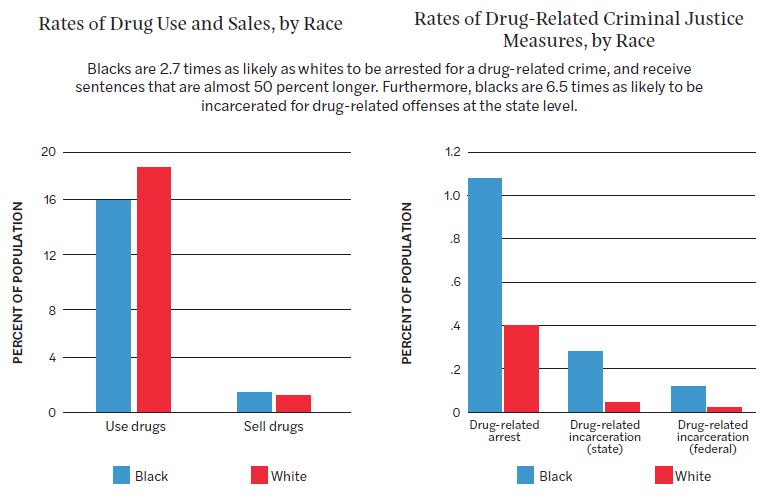

America’s mass incarceration does not affect all communities equally; Black men without high school diplomas are three times more likely to be imprisoned than white men of the same education level. And though Americans of all ethnicities use and sell illegal drugs at similar rates, black men are 2.7 times more likely to be arrested and 6.7 times more likely to be incarcerated than are whites. Black Americans also receive harsher sentences than whites when controlling for the seriousness of the offense and criminal history of the offender.

This report spotlights the way the criminal justice system treats those who lack political and financial power. We examine the effects of every stage of the system on our communities, highlighting how undemocratic policies and moneyed interests pervert justice and prey on the vulnerable, all while soaking up public funds desperately needed for other programs.

The policies and practices detailed in this report are a sampling – not a complete picture – of the dirty politics of mass criminalization. Past Common Cause work, such as Common Cause Maryland’s 2017 study of the bail bond industry’s pay-to-play politics, touched on portions of the system and future reports will focus on aspects of the prison industrial complex not covered in this report.

The influence of anti-democratic policies and the corrupting effects of corrections industry money are directly linked to mass criminalization and incarceration. Felony disenfranchisement – the denial of voting rights to persons with felony records – robs those most deeply affected by the system of a voice in changing it, while prison gerrymandering stacks the political deck against the medium-sized and large cities where most prisoners lived before running into the criminal justice system.

Meanwhile, the increasingly profitable industries that service many American prisons use their wealth and influence to obtain lucrative contracts, lobby for industry-friendly legislation, and help elect candidates supportive to their cause – more prisons filled with prisoners.

The effects of these forces are evident throughout the criminal justice system. People of color stopped by police often encounter officers incentivized to make more stops and more arrests to secure millions of dollars in local and state appropriations, federal grants, and asset forfeiture proceeds for their departments.

Those officers are enforcing laws passed by legislators influenced by prison industry campaign contributions and lobbying or by political imperatives – the need to be seen as “tough on crime” – in their re-election campaigns.

Arrested individuals may be charged by prosecutors and sentenced by judges who similarly seek harsher penalties under the pressures of re-election. And while in prison, citizens are at the mercy of powerful industries able to grossly overcharge them for a can of food or even a few moments with their families.

Despite this bleak picture, more examples of reform are emerging as Americans become aware of the realities of mass incarceration. It is an imposing, but not impossible democratic challenge..

MASS INCARCERATION UNDERMINES DEMOCRACY

Felony Disenfranchisement

Our government ought to work for everyone – but far too often, the legal system is working against us. Mass incarceration presents a unique democratic challenge: those most affected by it are unable to express their grievances at the ballot box. The culprit is felony disenfranchisement, the process by which an individual convicted of a felony loses the right to vote.

The practice has a long history; the British citizens who came to colonial America brought with them the policy of “civil death” – the loss of property, voting and other civil rights for those convicted of serious crimes and the tradition took hold. Today, most western-style democracies permit some or all convicted persons to vote while in prison, but only two U.S. states allow it.

As of 2016, 6.1 million incarcerated and formerly incarcerated Americans were legally denied the right to vote.

Felony disenfranchisement laws also have a racially tainted legacy; many were passed in South in the aftermath of the Civil War to exclude free black men from the ballot box. Even so, the Supreme Court has held that so long as the laws are facially neutral – applying to all persons convicted of felonies – they are valid and not subject to strict scrutiny – the most stringent standard of judicial review.

Until very recently, the racial impacts of felony disenfranchisement had not affected the legal analysis. But the impact is stark. Though only 1.8 percent of the non-black population of the United States is disenfranchised due to a felony conviction, the rate for African-Americans is 7.8 percent, more than four times higher.

While felony disenfranchisement laws have survived judicial scrutiny, they do not stand up to common sense tests. Traditionally, Americans have seen time in prison as an offender’s payment of a debt to society. People in prison retain their citizenship and we expect that having paid their debt, they will return to communities as productive citizens. But while calling on them to be good citizens, our system generally denies or erects barriers to their exercise of citizenship’s core right – the right to vote.

Most states give people with criminal convictions a pathway to recovering their rights, although the process is often burdensome. In 12 states however, people with felony convictions can never regain the right to…